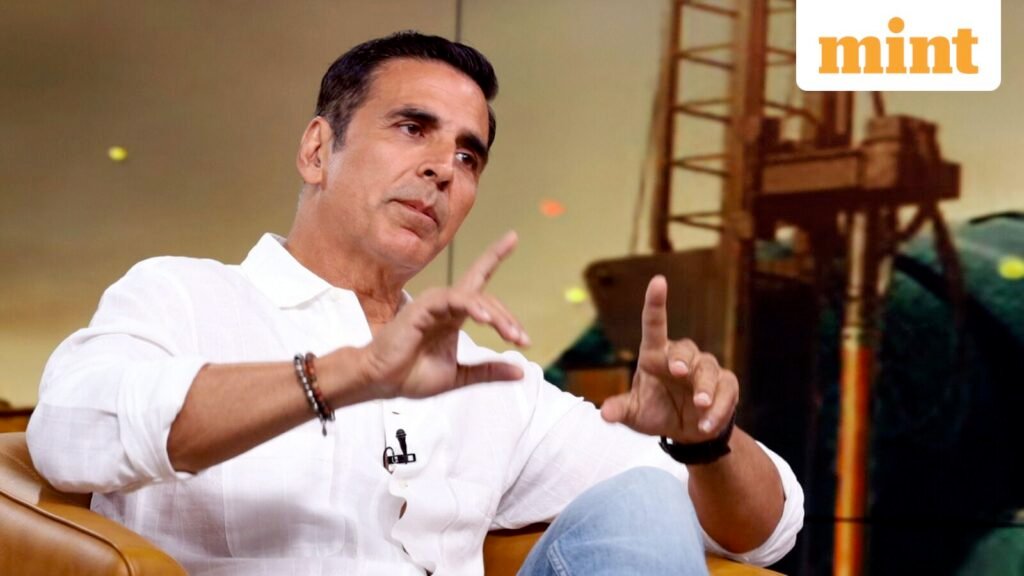

The issue came into limelight after Bollywood actor Akshay Kumar Bhatia approached the insolvency court to recover dues from Cue Learn, an edtech company. The case raised important questions about whether the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC) can be used as a debt recovery tool in business approval disputes.

Mint explains the NCLAT ruling and its long-term impact on celebrity brand contracts.

What sparked the dispute?

The case arose out of an endorsement deal signed in March 2021 between Akshay Kumar and Cue Learn. As part of the agreement, Kumar committed to provide promotional services for up to two days for a period of two years till March 2023. The total fee was ₹8.10 crore plus taxes, payable in two installments.

Cue Learn paid first ₹4.05 crore in March 2021 and the actor’s services were utilized for one day. Second installment ₹4.05 billion was due by April 2022. However, as the second day was never scheduled, the company did not make the second payment.

In April 2022, Kumar issued an invoice for the balance amount. After receiving no response, he issued a summons under the IBC in May 2022. Cue Learn responded that the second payment was associated with the use of its services on a different day and, as no such day was scheduled, no payment obligation arose.

In June 2022, Kumar filed a petition under Section 9 of the IBC. In January 2025, Delhi’s National Company Law Tribunal (NCLT) dismissed the suit, saying there was an earlier dispute over the interpretation of the contract. Kumar then appealed to the NCLAT.

Why did NCLAT dismiss the plea?

The NCLAT upheld the NCLT order and dismissed Akshay Kumar’s insolvency petition. Insolvency proceedings can only be initiated if the debt and default are clear and indisputable. If there is a genuine disagreement between the parties before the bankruptcy notice is issued, insolvency cannot be commenced.

The main issue was whether the second payment ₹4.05 crore was payable automatically as per the contract or whether it depended on the company actually using the actor’s services on the next day. Akshay claimed that the payment was due on a fixed date. Cue Learn claimed it was performance related and since it was never used the next day, no payment was due.

The Appellate Tribunal found that there was a genuine disagreement as to how the contract should be understood. The key question was whether the second payment had to be made automatically or only if the actor actually provided services on the second day. As the two parties had different but reasonable interpretations of the contract, the tribunal said that a genuine dispute existed before the insolvency case was filed.

The court also made a clear distinction between a claim and a debt, noting that while every debt is a claim, not every claim qualifies as a debt under the IBC.

The NCLAT also clarified that even if the matter amounts to a breach of contract, the proper remedy is a civil court or arbitration. Insolvency law cannot be used as a shortcut to enforce disputed contractual payments, he said.

What does the judgment mean for celebrities?

Legal experts said the ruling closes the insolvency route for most performance-related approval disputes. Raheel Patel, a partner at Gandhi Law Associates, said the decision “completely closes the door on celebrities using insolvency as a pressure tactic for endorsement or appearance fees”. Once a payment is contingent on performance, schedule, deliveries or contract interpretation, it ceases to be an operating debt under the IBC, he added.

Amit Tungare, managing partner of Asahi Legal, noted that most endorsement contracts are reciprocal, with payments tied to milestones or days of performance. “As long as a brand can make a genuine argument about the interpretation or planning of services, it can effectively protect itself from insolvency proceedings,” he said.

What options do celebrities have now?

Ankit Rajgarhia, designated partner at Bahuguna Law Associates, said that if celebrities want to retain insolvency as a legal option in future disputes, contracts must clearly state binding and unconditional payment terms. “To preserve insolvency as an option, the contract must specify binding, unconditional payment requirements with determinable deadlines,” he said.

According to Rajgarhia, payments should become due on specific dates regardless of performance terms. Structuring fees as clearly recognized written claims reduces the scope for interpretation disputes. He also suggested including acknowledgment of receipt once commitments are met and limiting the grounds on which brands can withhold payment to strengthen enforceability.

Experts have also suggested that celebrities include non-refundable signing bonuses, peg payments to clear dates rather than events, and add clauses that make late payments a permanent debt with limited grounds for withholding. If insolvency is not available, they can recover fees through civil litigation or arbitration, or seek interim relief such as a pre-judgment garnishment.

What does this mean for brands?

Lawyers said the ruling gives brands and manufacturing houses slightly more bargaining power – not because the companies are now free to default, but because they are insulated from the imminent threat of insolvency proceedings as a shortcut to recovery.

“The IBC was a powerful stick because the threat of losing control of the company often forced brands to settle quickly,” Tungare said. “With this threat removed from service-related disputes, brands now have the upper hand. They can withhold payment and force the celebrity into arbitration, knowing that the fast track to insolvency is blocked by the mere existence of a credible dispute.”