Many fitness enthusiasts often wonder: Should I focus more on planks or sit-ups? While both exercises are well-known, they approach core training in completely different ways.

The plank is an isometric exercise that emphasizes stability, postural control, and muscle endurance.

On the other hand, the sit-up is a dynamic movement that works the abdomen through spinal flexion, emphasizing mobility and contraction force.

Each method has its own set of benefits—and limitations—depending on your training goals, back health, and overall movement quality. This article will explore the differences between planks and sit-ups, covering topics like core activation, spine health, core strength, and functional performance, helping you decide which exercise best suits your routine.

Core Anatomy: What Are We Trying to Strengthen?

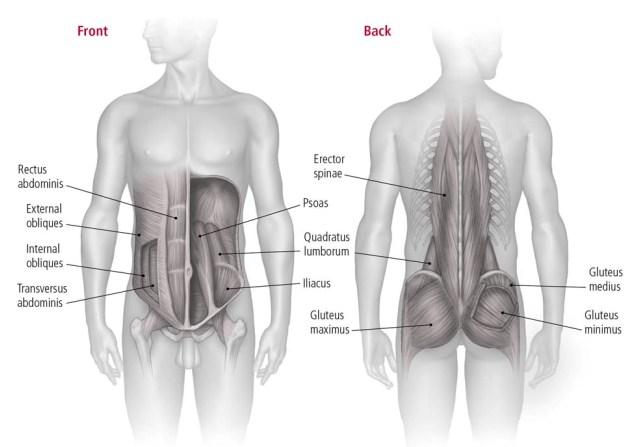

The term “core” encompasses more than just the visible abdominal muscles. The key components of the core include:

- Rectus abdominis – Responsible for trunk flexion and commonly activated during sit-ups.

- Transverse abdominis – A deep stabilizer that helps maintain intra-abdominal pressure during exercises like planks.

- Internal and external obliques – Assist with rotation, lateral flexion, and anti-rotational tasks.

- Erector spinae – Stabilizes the spine during dynamic movements.

- Multifidus, pelvic floor, and diaphragm – Often overlooked, these muscles are essential for postural control and spinal stabilization.

- Promotes spinal stability and reduces excessive lumbar movement.

- Trains the transverse abdominis and deep core muscles, which are difficult to target with dynamic exercises.

- Variations (e.g., side planks, RKC planks, elevated planks) can be safely modified.

- Offers high core endurance value with relatively low spinal compression.

- Builds dynamic strength in the abdominal musculature.

- Promotes active spinal flexion, which can improve mobility when performed correctly.

- Engages hip flexors and other trunk flexors, contributing to overall athletic movement.

- Planks maintain a neutral spine and are generally considered spine-safe, especially for individuals with existing back pain or disc issues.

- Sit-ups, particularly when performed with momentum or anchored legs, can increase lumbar compression and shear force. Repeated flexion, especially with poor form, may heighten the risk of disc herniation in susceptible individuals (McGill, 2007).

- If your goal is to build endurance, stability, and postural control for sports or long-term activities, planks and their variations are the better choice.

- If your goal is to develop strength and power through dynamic trunk movements, especially for sports like wrestling, gymnastics, or MMA, sit-ups and flexion-based exercises can still play a role—provided spinal integrity is maintained.

- Start with forearm planks, progressing to longer holds or weighted planks as endurance improves.

- Include side planks and bird dogs to target the posterior chain.

- Incorporate dynamic planks (e.g., shoulder taps, plank rows) for added challenge.

- Use controlled sit-up variations, such as Swiss ball sit-ups or hollow holds, sparingly and with strict form.

An effective core training program should address both movement and stability functions across the anterior, posterior, and lateral chains.

What Is a Plank?

A plank is an isometric exercise where you maintain a straight, rigid posture while supporting your weight on your forearms and feet. Your spine remains in a neutral position, and the muscles of the anterior core are engaged without any joint movement.

Key Benefits of Planks:

Planks are widely used in rehabilitation, athletic training, and general fitness for their low injury risk and versatility.

What Is a Sit-Up?

The sit-up is a classic trunk flexion exercise where the exerciser starts in a supine position and raises their torso toward their knees. It primarily targets the rectus abdominis and, to a lesser extent, the hip flexors such as the iliopsoas and rectus femoris.

Benefits of Sit-ups:

However, sit-ups also involve repeated spinal flexion under load, raising concerns about lumbar disc stress when performed incorrectly or excessively.

Muscle Activation Comparison

| Exercise | Primary Muscles Worked | Type of Contraction |

|---|---|---|

| Plank | Transverse abdominis, rectus abdominis, obliques, multifidus | Isometric (static hold) |

| Sit-up | Rectus abdominis, hip flexors, obliques | Dynamic (concentric/eccentric) |

While both exercises activate the core, the plank excels in developing static postural strength and deep core muscle recruitment, whereas the sit-up focuses more on power-based strength in the rectus abdominis.

Spinal Health and Injury Risk

This is perhaps the most debated aspect of the plank vs. sit-up comparison.

According to spine biomechanics expert Dr. Stuart McGill, planks are preferred for developing core stability without compromising spinal health, while sit-ups may be contraindicated for certain populations.

Core Endurance vs. Core Strength: What’s Your Goal?

A well-rounded program can include both, but planks offer more versatility and lower risk for the general population.

Programming Recommendations

For Beginners or Those with Back Pain:

For Athletes or Advanced Lifters:

Weekly Core Plan Example:

| Day | Exercises | Sets × Duration/Reps |

|---|---|---|

| Monday | Front plank hold | 3 × 30-60 seconds |

| Wednesday | Side plank (each side) | 3 × 30 seconds |

| Friday | Hollow hold or controlled sit-up | 3 × 10–12 slow, controlled reps |

Conclusion: Which Builds a Stronger Core?

Both planks and sit-ups offer benefits—but they serve different purposes. For most individuals, especially those concerned with spinal health, postural endurance, or functional movement, planks are the superior choice. They build deep core stability, reduce injury risk, and enhance athletic performance across various sports and activities.

Sit-ups can still be useful for dynamically targeting the rectus abdominis but should be approached with caution, particularly if lumbar health is a concern. Ultimately, the best core training programs integrate isometric and dynamic elements, balancing stability with mobility to create a durable and well-rounded midsection.

References

- McGill, S. M. (2007). Low Back Disorders: Evidence-Based Prevention and Rehabilitation. Human Kinetics.

- Ekstrom, R. A., Donatelli, R. A., & Carp, K. C. (2007). Electromyographic analysis of core trunk, hip, and thigh muscles during 9 rehabilitation exercises. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther, 37(12), 754–762.

- Axler, C. T., & McGill, S. M. (1997). Low back loads over a variety of abdominal exercises: Searching for the safest abdominal challenge. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 29(6), 804–811.

- Willardson, J. M. (2007). Core stability training: Applications to sports conditioning programs. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 21(3), 979–985.

- Schoenfeld, B. J. (2010). The mechanisms of muscle hypertrophy and their application to resistance training. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 24(10), 2857–2872.