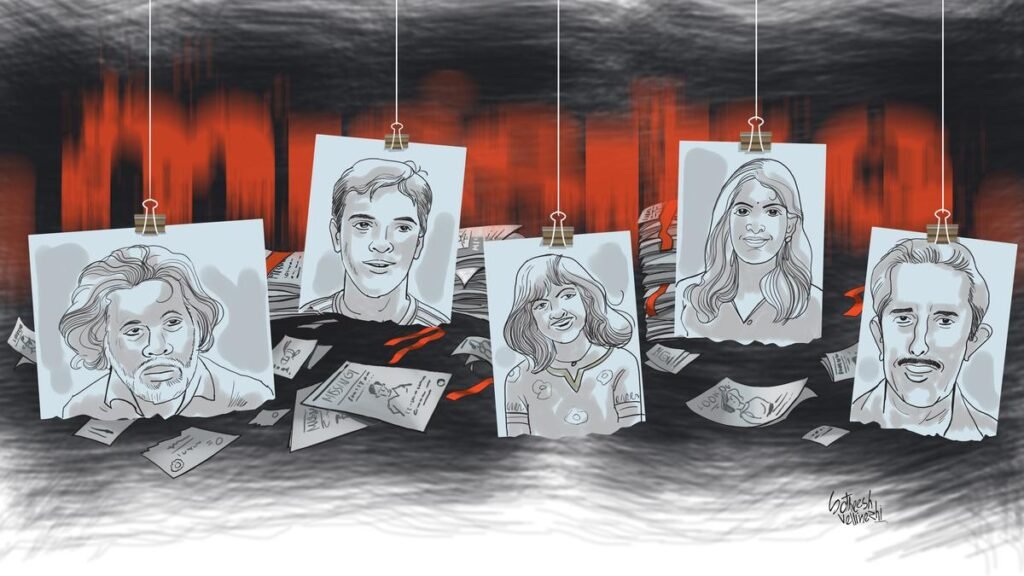

A newly printed photograph of Thomas John, a 42-year-old farmer, hangs on the wall of Pazhamchirayil House, a small concrete residence in Kavumkudi, near Alakode, in Kannur district.

Simi, his wife and their three children have yet to come to terms with their sudden loss. She has yet to overcome the grief of losing her husband. She is still haunted by thoughts of her life partner who went missing in November last year only to be found dead by the river.

“Within hours of confirming his disappearance, we approached the local police station. As he was upset about paying off his debt in the previous weeks, we were worried when he just disappeared,” recalls Simi, who complains that the police refused to take her complaint seriously. “If the police had reacted quickly, he would be with us now,” he says.

Simi complains that the police delayed the search on the reported grounds that they could not track the location of his mobile phone. “They said that the search can be started only after waiting for at least 24 hours. Because of their indifference, we searched with the support of the residents. Unfortunately, we found him dead the same day,” he wails.

The latest figures from the police confirm that the state has seen a sharp increase in cases of missing persons over the past five years. Official data shows that 8,742 missing persons were registered in 2020. It increased to 9,713 in 2021 and 11,259 in 2022. The next year it was 11,760 and 11,897 in 2024.

“Despite the high number of missing persons, Kerala maintains a relatively high success rate in tracing them. Early reporting of cases and a proactive approach by the police make the difference,” says a senior police officer with the Anti-Human Trafficking Unit (AHTU) in Kerala.

Uneven trends in the number of missing cases are evident from district-level data compiled by the State Crime Records Bureau. In the rural areas of Thiruvananthapuram district, the number of missing cases has shown an increasing trend in the last few years. The total number of cases, which was 630 in 2022, almost doubled to 1,177 in 2023. However, there was a slight decrease in 2024.

Rural areas of Ernakulam district also witnessed an upward trend from 508 in 2020 to 892 in 2023. Later, the numbers declined slightly to 648 in 2024. In Idukki, the police registered more than 1,000 missing cases in 2023. In North Kerala, districts like Kannur (rural resources) are lower.

Missing children

Cases of missing children also remain a subject of interest to law enforcement authorities.

According to the Crime Records Bureau, more than 10,000 cases of missing children have been reported in Kerala in the last five years, though most of the children have been traced. Police and families have no idea about the more than 500 missing children who have been unaccounted for since they disappeared. Family disputes, relationship and financial problems and the influence of social media are contributing factors to their disappearance, police say.

“Delayed reporting of incidents, lack of real-time integrated database and jurisdictional restrictions often hamper investigations in the early stages,” says S. Muraleedharan, a retired police officer who worked with the AHTU unit.

With the number of missing persons cases on the rise, there is a need for early registration of complaints, better data sharing mechanisms, coordination between government and law enforcement agencies and greater public awareness, he points out.

Police officers with the Regional Crime Squad admit that late reporting is one of the most important obstacles in the investigation of missing persons. In many cases, families are advised to wait some time before filing a complaint, especially when an adult is missing. Investigators believe this practice could delay the investigation.

“Investigations within the first few hours of a person’s disappearance are often critical in gathering digital evidence, tracking their movements and identifying potential witnesses,” notes S Ranjith, a police officer with the High-Tech Crime Investigation Cell. He points out that the delay could lead to the loss of cell phone data, surveillance footage and other time-sensitive information crucial to the investigation.

A significant number of missing persons cases in Kerala involve adolescents and young adults. Figures from districts such as Kozhikode, Ernakulam and Thiruvananthapuram show that individuals between the ages of 16 and 25 account for the major share of reported disappearances.

“Many of these cases eventually turn out to be cases of absconding, voluntary departure or temporary estrangement from families,” says a senior police inspector involved in investigating several such cases in Kozhikode. She noticed that cyber interactions, exposure to unfamiliar networks, and rash decision-making often end up in family conflicts that provoke children to leave home.

“Girls represent a high number of reported missing cases. Many girls leave their homes due to failed personal relationships or family disputes. They are vulnerable to sexual exploitation, human trafficking or other forms of abuse,” says a former member of the Committee for the Protection of Children. He says the cases of missing children from various shelters under government control need to be seriously investigated.

A. Nireesh, a former child helpline co-ordinator, says the factors that trigger the disappearance of people, especially children, need to be investigated. He suggests that there should be programs for the long-term protection, counseling and rehabilitation of these persons.

Human rights defenders also point out that in at least a few cases of disappearances, criminal elements could be involved. One such case is the missing case of K. Hemachandran, a native of Wayanad temporarily residing in Kozhikode city.

Hemachandran, who ran a private chit fund in the city, went missing in August 2023. After 16 months, police managed to solve the mystery surrounding the businessman’s disappearance. The police found that he had been murdered and the body buried.

“Hemachandran was kidnapped and murdered after some financial disputes. His body was found in a forest area in Cherambadi, Tamil Nadu, where it was buried,” says a senior police officer who was part of the investigation team.

Hemachandran’s family members say a leaked phone conversation of one of his kidnappers helped crack the case. However, he claims that a focused probe would help in solving the case.

In contrast, there are many high-profile cases that still remain mysterious. There is still no sign of the disappearance of prominent realtor Mohammed Attoor alias Mami from Kozhikode in 2023. A two-year investigation, initially by the local police and later by the crime branch, failed to solve the mystery. Despite extensive questioning involving nearly 200 people connected to Mami and other investigations, a breakthrough remained elusive.

P. Rajeevan, Mami’s friend, fears that he might have been kidnapped. He blames the police for not investigating the case prudently.

Drug connection

Cases of substance abuse have also been identified, contributing to the growing number of missing persons. It was only after a five-year investigation into the disappearance of 35-year-old Vijil from Elathur that the police managed to state that it was a case of drug overdose death. His friends allegedly buried him to cover up the incident rather than report it to the police.

Police believe that drug-related deaths are an under-recognized factor in missing persons cases. They point out that this often involves hiding driven by fear and misinformation.

“When missing persons move from one place to another, tracking them becomes difficult due to lack of coordination between agencies based in different places. Absence of a unified real-time missing person tracking system often leads to the generation of fragmented information,” says an IT expert from the police cyber cell. He also points out that the shortage of hands, heavy workload and increasing number of cybercrime are limiting the operational capacity of the police.

Professional counselors, who often deal with the rehabilitation of missing persons, believe that there should be a shift in the approach to the treatment of persons. According to them, when faced with a complaint, the police often first examine the procedural aspects of the case rather than understanding the complainant’s concerns and the need for swift action. A speedy investigation should be ensured with all supporting agencies to trace the missing person. Proactive intervention is often needed to help victims reintegrate into society.

Psychologists A. Dhanya and PV Jincy argue that interventions should be made to remove the procedural and technical obstacles associated with tracing and rehabilitating missing persons.