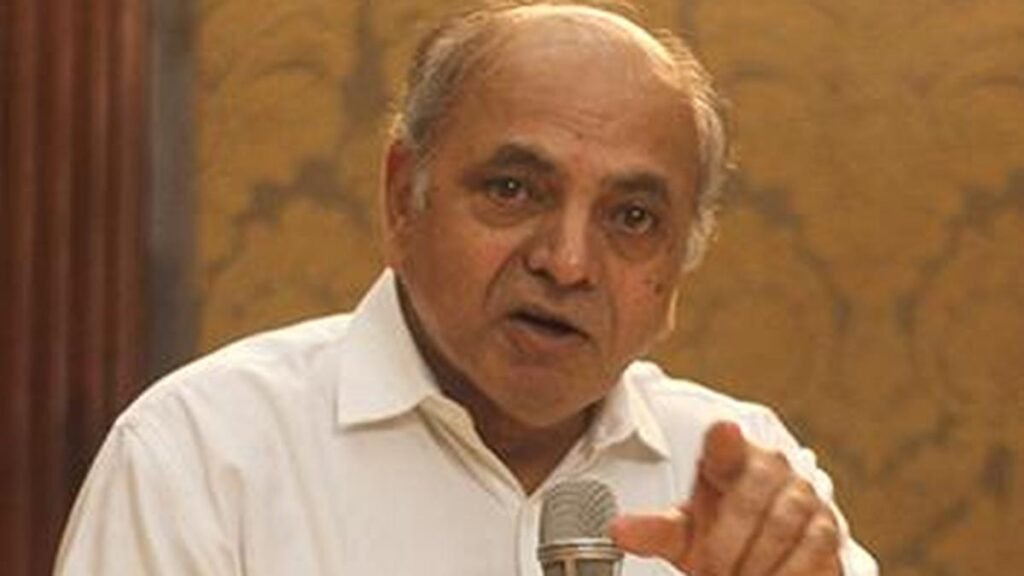

A renowned scholar and linguist, Dr. Ganesh Deva. File | Photo credit: Supreet Sapkal

Linguistic and cultural indicators could hold the key to solving the caste enumeration puzzle, says scientist, linguist, author and cultural activist Professor GN Devy. In an exclusive interview with The Hindu, he explained that even if residents entered what they thought was their caste name, post-census studies and carefully layered investigations could analyze features of language, ancestry, lifestyle and kinship to arrive at a complete list of castes that correspond to all groups, while also being able to account for duplications, name variations and spelling.

“This model has been tried and tested for languages,” said Professor Devy, whose work leading the Peoples’ Linguistic Survey of India project has led to the documentation of more than 780 languages in the country.

The Union government plans to conduct the next census in 2026 and 2027. The first phase — the list of properties — is expected to be completed this year; the second phase – population census (with caste) – is scheduled to take place in 2027. However, the methodology for the caste census has not yet been announced by the Office of the Registrar General and the Census Commissioner of India.

There are discussions among activists, scholars and community leaders about two possible methods: the first is to leave the field open in the form of a census – what the Socio-Economic and Caste Census (SECC) did in 2011; and the other is to compile a list of castes from which people can choose – which Bihar’s Caste-based Survey did. The argument for the latter often draws its strength from the fact that the SECC 2011 eventually returned more than 46 thousand caste names.

A post-census study is essential

Speaking to The Hindu, Professor Devy argued in favor of the first method and said that the survey and language enumeration methodologies could be used to condense not only the 2011 SECC data but also data from the upcoming census. But he noted that this would require the government to keep the data open to scrutiny by scientists and involve institutions such as the Anthropological Survey of India (AnSI).

Explaining the approach, Professor Devy said the process can start by gathering information about mother tongues. “The 2011 census returned 19,000 mother tongues. But this was subjected to several layers of checking to account for duplication, spelling variations, errors and yet another layer to filter out those with verified grammar. This narrowed the list down to 1,369 mother tongue languages,” he said.

Using the example of community classification, he continued: “Similarly, there is a community called Sansi in Punjab. The same community is called Kanjar in Rajasthan, Chhara in Gujarat and Kanjar Bhat in Maharashtra. But they are one community because they have a shared language called Bhaktu. So even if the census returns four names, it may point to a common language, related lifestyle, kinship, ance.” An Anthropological Survey of India can confirm this.’

Professor Devy added that works such as AnSI’s ‘People of India’ project could be a reference point.

Number of DNTs needed

Professor Devy, a scholar who co-founded the Denotified, Nomadic and Semi-Nomadic Tribes Rights Action Group (DNT-RAG) with author Mahasweta Devi and chaired the government’s Technical Advisory Group on DNT in 2006, said the Census Bureau must declare its intention to explicitly count DNT communities, classified as criminal criminals, as Crera communities. 1871).

He noted that if this opportunity is not taken, India risks alienating more than 10 million people, a “problem that may be much bigger than the problem of calculating, tabulating and making a proper list”.

Published – 08 Feb 2026 20:02 IST