Mukesh Jaji calls himself a “writer, storyteller, dream spinner” on social media. About 50 km north of Delhi, India’s capital, he sits on a charpoy leaning against a wall in his farm studio on the outskirts of Sonipat. Green fields of prosperity surround the 32-year-old bespectacled lyricist who writes Haryanvi songs.

Mukesh Jaji (seated) with his nephew and singer Aman Jaji at Jaji village in Sonipat district of Haryana. , Photo credit: SHIV KUMAR PUSHPAKAR

Confined to a wheelchair for ten years after a road accident, he talks about the rapid growth of Haryana’s music industry over the past decade. “Pehle Haryana mein shadiyon mein dus gane Punjabi do ek Haryanvi bajta tha. Ab ulta ho gaya hai! Ab dus Haryanvi do ek Punjabi bajta hai, (Earlier in Haryana, at every wedding, 10 Punjabi songs now played for every Haryanvi1.0 Punjabi song),” he says.

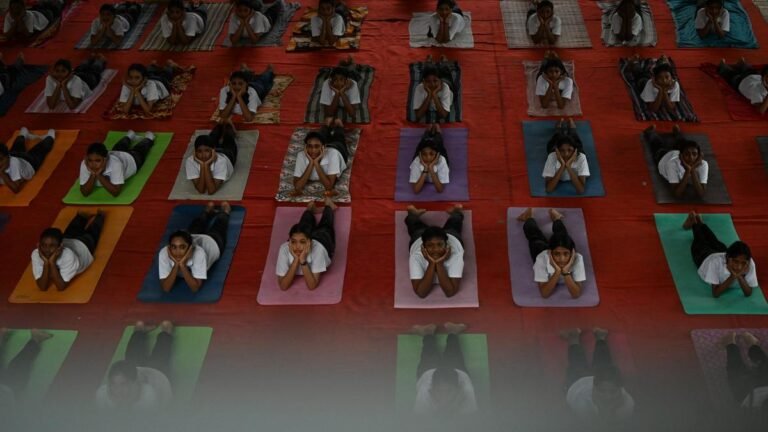

Two Haryanvi chartbusters ’52 Gaj Ka Daman’ (52 Feet Skirt) and ‘Chatak Matak’ (Smart Woman) were released five years ago amid the pandemic. To date, both of them, sung by Renuka Panwar, have over 1 billion views on YouTube. Mukesh, who wrote ’52 Gaj…’, says there is a shift in the state’s regional music scene.

Also read | From mofusil towns to the World Cup stadium: witness the quiet rise of H-pop or Hindutva pop

The music video featured Pranjal Dahiya, a Haryanvi actor and social media influencer, while “Chatak…” featured Sapna Choudhary, an actor and performer. Both have over 5 million followers on Instagram, while Mukesh has written around 120 songs, 40 of which have crossed the 1 million stream mark.

Both music videos feature women wearing traditional frilly skirts and shin-length shirts with dupattas covering their heads. Now major music players like Saregama India Limited, T-Series and Sony Music are producing and distributing Haryanvi songs on streaming platforms like JioSaavn, Spotify, Gaana and Apple Music.

Pop music and money

This boom has resulted in local musicians earning 10 to 100 times more than they would have 5-10 years ago. Mukesh himself charges up to ₹10 crore for writing a song. “Earlier, artists from Punjab used to look down on those from Haryana. Now they are eager to collaborate,” he says, using social media that talks about collaboration.

Kuldeep Rathee, Music Video Director. , Photo credit: SHIV KUMAR PUSHPAKAR

Kuldeep Rathee, who has directed songs like the 2019 hit ‘Rx 100’ with muscle men, reveals that budgets for the shoot have jumped from ₹20,000 to ₹20,000.

“Earlier, we shot in one location with basic cameras. The actors brought their own costumes. Now we go for it: multiple locations, 2-3 day shoot, Bollywood-level cameras with up to ₹35,000 a day rental, costume designers and choreographers. It’s a whole production,” he explains. “The influx of cash is attracting top talent. Skilled professionals are joining Haryanvi music; the industry is booming,” says Rathee.

Musicians also wear Haryana on their sleeve. Shiva Choudhary, for example, sings ‘Belong to Haryana’, celebrating its agrarian, rugged culture: “We belong to Haryana and we are Jats. We believe only in the rule of khaps (community leaders) and fear no one. We are in this world to have fun. We are not afraid of police stations and checkpoints. We drink freely and we don’t drink. Her songs top the charts on VYRL Haryanvi performers who sing in that language.

With this generational shift, guns, gangs and hooliganism are part of the songs. Ten songs by Masoom Sharma, one of Haryanvi’s most popular singers, including ‘Chambal Ke Daku’, ‘Tuition Badmaashi Ka’ and ‘Jailer’, have collectively clocked over 100 million views. Dhand Nyoliwala’s ‘Illegal’ has amassed over 2.2 million views within days of its release in 2024. Despite the success of the genre, the celebration of violence in music has drawn criticism.

The plot and lyrics of some songs present the police and the judiciary in a bad light, while portraying larger-than-life main protagonists as more powerful than law enforcement. For example, “Tuition Badmashi Kaa” depicts a policewoman who is hit by the protagonist, a wrestler-turned-criminal. Every time she and her power try to catch the male lead, he tricks her and runs away.

The video of another controversial song “Court Mein Goli”, released in 2022, shows a dramatic scene where the protagonist shoots a witness inside the courtroom in the presence of the police and the judge who is hiding behind the bench. In 2023, a Public Interest Litigation was filed in the Gujarat High Court claiming that the song “targeted the integrity of the judicial system” and sought its removal from YouTube.

Over the years, there have been many incidents of firing inside court complexes, including Bhiwani, Ambala, Hisar and Gurugram. This has raised concerns about the impact of songs that seem to celebrate gun violence and culture.

In 2019, a Punjab and Haryana court order, responding to five writ petitions, said: “The court may also take cognizance of the fact that the glorification of liquor, wine, drugs and violence in songs in the states of Punjab, Haryana and the Union Territory of Chandigarh has increased recently. These songs affect children of impressionable age.”

In a 30-page order, the court directed the director generals of police in the two states and the UT to “ensure that no songs glorifying alcohol, wine, drugs and violence … even in live performances are played”.

Murder at a wedding

Panditrao Dharennavar, 51, an associate professor of sociology at a government college in Chandigarh, moved the court against songs promoting violence following the December 2016 murder of a 23-year-old dancer at a wedding in Punjab’s Bhatinda.

Dharennavar, originally from Karnataka, was posted to Chandigarh after being appointed by the UPSC exam more than two decades ago. He was gradually attracted to the local language, literature and culture.

“I felt very sad about the incident. As a teacher, I thought it couldn’t be true Punjabi culture: a woman dancing at night at a wedding and being shot by a guest in excitement while Diljit Dosanjh’s song ‘Shraab Wargi’ was playing,” says Dharennavar.

He prepared the petition for two reasons: the noise and the theme of the songs. All three governments – Haryana, Punjab and Chandigarh – were involved in the case. “There were more than 15 hearings over three years before the judgment was delivered in 2019,” says Dharennavar. “A question was raised about vulgar songs being played on online platforms as well. Although the court did not specifically mention the ban online or offline in its decision, the meaning of the order is that such songs should not be played anywhere, be it live performances, internet or any other platform.”

Downloaded songs

Over the past two years, the Haryana Police has asked YouTube and other social media platforms to take down about 60 songs that allegedly promoted violence and gun culture, says Inspector General of Police, Special Task Force, Satheesh Balan. It was part of an effort to de-glorify crime in Haryana.

While the impact of such songs is hard to quantify, Balan notes that some may be influenced by content that encourages aggressive masculinity.

In 2025, two concerts, including one in Gurugram, were suspended for playing these songs. However, the event drew strong protests from the music industry, with some artists accusing the police of targeting several singers. Masoom Sharma appeared on various platforms and said that there were hundreds of songs promoting violence, but the police asked for the withdrawal of the six songs he had sung. He hinted at a conspiracy.

Social media creator Rakhi Lohchab, with more than 6,000 followers on her Instagram account, also supported the singer and posted videos demanding that the police act in an unbiased manner.

In the 2025 monsoon session of the Haryana Assembly, Shahdara Congress MLA Ramkaran Kal sought Chief Minister Nayab Singh Saini’s statement on the “excessive” deletion of songs against three singers: Masoom Sharma, Narendra Bhagana and Ankit Baliyan. Social Justice Minister Krishan Kumar said these singers “have done a lot for the pride of Haryana” and asked the CM to take a sympathetic view.

However, many “deleted” songs are still available online. Dharennavar says the police delete songs from the original accounts of singers and production companies, but seem powerless to remove them from many other accounts. “For songs forwarded from many other accounts, it is people’s social responsibility to file a formal complaint with the police or relevant authorities and ask for action,” he says.

He talks about FM radio stations in and around Chandigarh continuing to play banned songs despite court orders, prompting him to write to the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting. The Union Government then issued a recommendation in 2022.

Dharennavar says that there is violent and vulgar content in the songs across Haryanvi, Punjabi and Bhojpuri. “After some parliamentarians and representatives of organizations received these references, the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting has written to publishers of online curated content and self-regulatory bodies of OTT platforms to comply with Indian laws and adhere to the code of ethics under the Information Technology (Guidelines for Intermediaries and Digital Media Code of Ethics) Rules, 2021,” says Dharennavar.

The Special Task Force held a meeting with the music industry to highlight the risks of promoting violence not only to society but also to the artists themselves.

Balan says some artists who gain fame through such content end up as victims, receiving requests – or threats – from gangsters to make songs praising them, or selling them content at low prices, which is then posted on gangster-owned Benami channels for profit.

“Several months after the police meeting, copywriters avoided such content, but the trend has resurfaced. However, now the plot has been tweaked to show that truth and goodness will prevail in the end,” observes Mukesh. He wrote several reflective songs, including ‘Maa Babu’, as well as compositions on topics such as cows, the army and inter-caste marriage. However, these failed to gain the audience’s attention. “I write two or three such songs a year. My peers do too, but it’s largely for personal fulfillment. These songs don’t generate income. They’re high-energy songs with provocative lyrics and themes of indulgence and aggression that resonate with the youth,” he says.

“Jo thali chahiye parosani padegi, nahi to koi restaurant mein nahi aayega (We will have to serve the plate that the customer wants, otherwise no one will come to the restaurant),” says Mukesh.

ashok.kumar@thehindu.co.in

edited by Sunalini Mathew