Tamil Nadu contributed to constitution making not only through prominent personalities but also common people.

The contributions were not only in a positive sense of rights, but also in a negative sense. Guarantees for vulnerable sections of society such as the Scheduled Castes (SC) and religious minorities have been a memorable feature of the state’s contributions.

It all started when the Sub-Committee on Minorities of the Advisory Committee to the Constituent Assembly (CA) issued a six-point questionnaire in March 1947 to ascertain the views of individuals and institutions on the issue of minority protection in the Constitution, according to a report in The Hindu on March 9, 1947. The panel was chaired by Muk Jagherji, Christian HC. Ram, C. Rajagopalachari (CR), Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, BR Ambedkar, SP Mookherjee, Rajkumari Amrit Kaur, M. Rutnaswami, KM Munshi and Govind Ballabh Pant.

It was left to VI Munuswami Pillai, who was the Minister of Agriculture in the Council of Ministers headed by the CR in the Madras Presidency during July 1937-October 1939, and his SC colleagues to demand the implementation of the concept of maintaining the reservation system in education and employment for the Scheduled Castes for a period of 10 years (to be renewed every 10 years). Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, the first Deputy Prime Minister of independent India and head of the Advisory Committee, accepted the demand and incorporated it in a report submitted to the CA in May 1949 for consideration.

The idea of a separate electorate for minorities figured in the meetings of the Subcommittee on Minorities and the Advisory Committee. As late as July 1947, the Advisory Committee agreed with the sub-committee’s view that there should be no separate electorates for minorities.

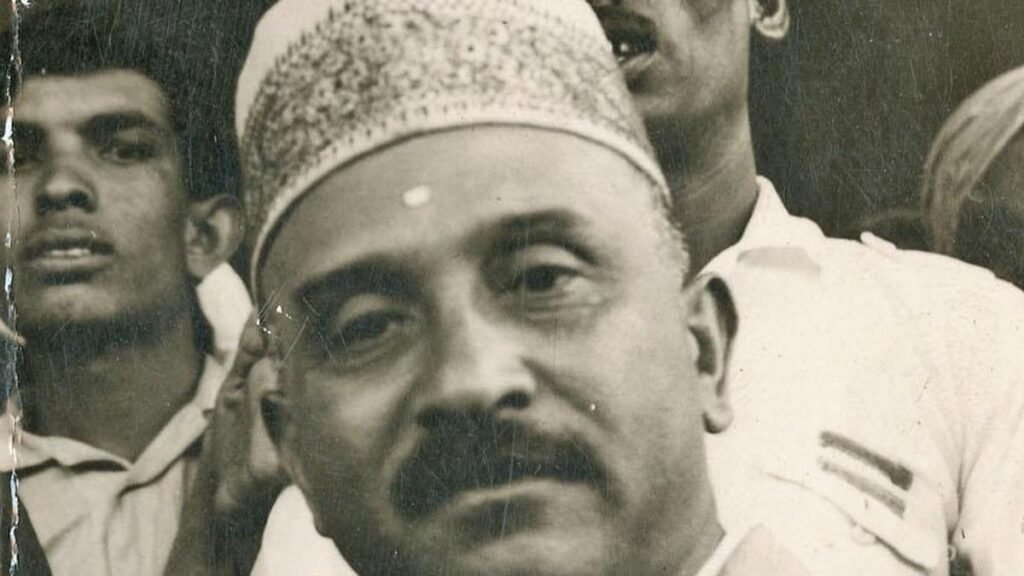

Mohammed Ismail (Muslim League) and his colleague B. Pocker Sahib Bahadur, both from the state, were big voters for separate electorates. Pocker Sahib Bahadur argued that the minorities must have a way to voice their grievances. It was for this purpose that separate representation was sought, and when the reservation scheme was abandoned, the question of a separate electorate “automatically” arose, said a report of this newspaper on 26 May 1949. Ismail argued that “what we want is the right of self-expression, the right to be heard and the right to association. It is not another device to separate people.”

However, the Sub-Committee on Minorities rejected the idea of a separate electorate. ZH Lari, who was the League representative from the then United Provinces (now Uttar Pradesh), emphasized that there should be no provision to isolate one section of the people from the mainstream of public life. Minorities must strive to become an integral part of the nation. They should demand only such guarantees as were consistent with this aspiration, calculated to give them an honorable place in the administration of the country, not as a separate independent entity, but as a welcome part of the organic whole.

CA received ideas from ordinary citizens who emphasized both positive and negative perspectives. Advocate General of the Madras High Court, KV Sundaresa Iyer, opined that if the constitution “provided some degree of immunity and protection to community customs and culture from unjust legal encroachment”, each community would feel secure in its place “notionally if not geographically,” said an article titled “The People and the Making of India’s Constitution” published by Cambridge University on January 2. justification for the government’s entry “into the field of communal meals or dowry, which is a purely personal and economic question”. However, in the spirit of republicanism, the framers of the constitution rightly rejected Iyer’s idea.

An individual, S. Oppiliappan, a resident of Kattunedungulam village in Sivaganga district, sent a handwritten memorandum in Tamil to the CA Secretariat in accordance with “Assembling India’s Constitution”, a recent publication from Penguin Random House. Although the CA Secretariat and the Press Information Bureau were headed by two Tamilians (HVR Iyengar and AS Iyengar), they were able to identify the key points of the sender of the memo with great difficulty. The authorities could not determine the community to which the author belonged, but speculated that he could be a Hindu SC or Dalit. Oppiliappan’s main demand was for members of his community to have freedom of worship and autonomy in managing their own community, the publication said.

The broad sense of freedom sought by the people of Kattuedungulam was enshrined in Article 25, which is entitled Right to Freedom of Religion. Subject to certain restrictions such as public order and morality, the article states that “all persons have an equal right to freedom of conscience and the right freely to profess, practice and propagate religion”.

The people of this country, especially the youth, must remember that the Constitution is the result not only of the collective efforts of eminent legal personalities and political leaders, but also of persons like Oppiliappan.

Published – 18 Feb 2026 07:00 IST