Here are two questions for cricket fans:

Which team did India play in the semi-final of the 2003 Cricket World Cup?

When did India and Pakistan meet for the first time in the Cricket World Cup?

If you know the answers, you understand the long history of experimentation and structural errors in ICC tournament formats.

Comedy from 2026

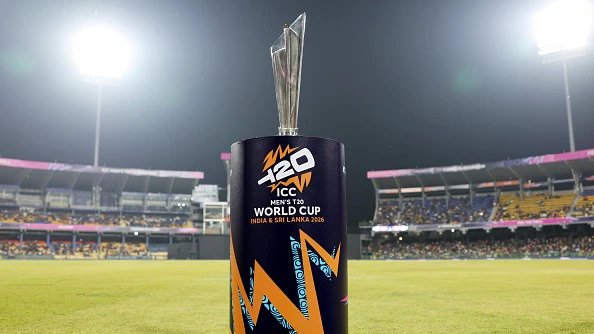

Something structurally absurd has happened at the 2026 Under-20 World Cup in India and Sri Lanka. All four group winners – India, Zimbabwe, South Africa and West Indies – finished in the same Super Eight group. Meanwhile, the runners-up face off in what appears to be a comparatively easier Super Eight group.

In other words, the FIFA T20 World Cup 2026 has created a scenario where topping the group effectively punishes you.

That’s not bad luck. It’s not a draw joke. It is a direct result of pre-seeding, a mechanism whereby Super Eight groups are determined by ICC rankings established before the tournament begins, rather than actual group stage placings.

As a result, the group stage becomes less of a competition and more of a planning exercise. Target positions are effectively shaped in boardrooms before the first ball is hit.

Why does pre-cultivation exist? Because it allows broadcasters to lock in schedules months in advance. It guarantees battles between the marquees – primarily India and Pakistan – regardless of what happens in the group stage.

It ensures that India’s Super Eight matches can be sold to advertisers even before the tournament begins. This is commercial engineering disguised as tournament design. And the group stage is becoming less about merit and more about elimination – especially of the associated nations – with occasional collateral damage such as Australia’s exit this year.

A consistent pattern

Throughout the history of the ODI World Cup and later the T20 World Cup, the ICC has repeatedly tinkered with formats – tweaking, twisting and experimenting – often sacrificing clarity for commercial logic.

First ODI World Cups (1975–1987)

Until the 1987 ODI World Cup, the structure was simple: eight teams divided into two groups, the top two advancing to the semi-finals.

Error? Not every team played each other.

Most absurd consequence: India and Pakistan did not meet in an ODI World Cup match until 1992. In 1975, 1979, 1983 and 1987, the two fiercest rivals were repeatedly placed in separate groups and sometimes eliminated without facing each other.

ODI World Cup 1992: The Benchmark

The ICC perfected it in the 1992 ODI World Cup.

Nine teams. Full round. Top four to semi-finals.

Every team played every other team. Pure run speed was important from the first game. No space to drive. Structurally, it was the most honest ODI World Cup ever staged.

The rain rule was infamous – South Africa’s revised target of 22 from 1 ball – but the format itself was unassailable.

Everything that followed was pretty much a departure from that standard.

ODI World Cup 1996: The thinning begins

Expanded to 12 teams in two groups of six, with four from each group advancing to the quarter-finals.

Four of the six qualifiers meant that teams could lose twice and still progress comfortably. The urgency of 1992 has evaporated.

India defeated Pakistan in the quarter finals. Sri Lanka defeated India in the semi-finals. India later cited fatigue. However, that is another story.

1999 ODI World Cup: The Super Six Confusion

The Super Six was introduced. The top three from each group advanced and carried their results against the other qualifiers.

The system was so convoluted that even dedicated fans struggled to follow the order.

India progressed with just two points carried, despite losses to the other qualifiers. A few more defeats ended their campaign.

Australia dominated and won every Super Six match. When a champion wins it all, structural flaws fade into the background. But South Africa’s tie in the semi-final – Lance Klusener’s dismissal, run out – took place under this confusing system.

A format that managed to eliminate a team in the run after a tied semi-final, in a tournament that few fully understood, was deeply flawed.

ODI World Cup 2003: The Super Six Returns

Fourteen teams. Same Super Six logic. The same opaque order.

Pakistan, England, West Indies and South Africa were eliminated early. Kenya reached the semi-finals and played India – a real fairytale.

But most fans struggled to explain how Kenya progressed. At this point, the ICC clearly prioritized match volume and broadcast revenue over structural clarity.

ODI World Cup 2007: The Nadir

Sixteen teams. Four groups of four. The best two to the Super Eight. Top four to semi-finals.

Forty seven days. Seven weeks.

India and Pakistan were eliminated in the group stage. Super Osmička once again moved the results forward. The final in Barbados ended almost in darkness.

Widely regarded as the worst ODI World Cup ever staged – and deservedly so.

It even included a murder investigation.

2011 and 2015 ODI World Cups: Stability returns

Two groups. Quarter finals. Semifinal. Clean and clear.

Could you describe the format to someone new to cricket. Both tournaments brought thrilling drama. India clinched their second ODI World Cup 2011. (Photo: Reuters)

For once, the ICC showed restraint and retained the same structure twice.

2019 & 2023 ODI World Cups: Round Robin Confirmed

Ten teams. Full round. Top four to semi-finals.

The closest the ODI World Cup came to integrity was 1992.

Every game mattered. Pure running speed was decisive. No carried points. No opaque seeding.

The 2019 final – tied match, Super Over tie, decided on number of boundaries – remains one of the greatest in cricket history.

The 2023 edition was equally coherent. The ICC got it right twice in a row.

Development of T20 World Cup

Early T20 World Cup (2007–2016)

The early T20 World Cup was imperfect but fair.

Simple groups. Super eights or super fours. Pure order.

The 2007 bowl-out rule was controversial, but structurally the tournaments were understandable. Australia won the 2007 T20 World Cup. (Photo: Getty)

T20 World Cup 2021 and 2022: The Super 12 Era

Sixteen teams. Qualifying round. Two groups of six. Top two to semi-finals.

It was bloated but clear. No carried over results. No pre-cultivation.

England’s 2022 title made them the first team to host the ODI and T20 World Cups simultaneously – achieved in a format that respected competitive clarity.

T20 World Cup 2024: A structural shift

Expanded to 20 teams. Performance of the Super Eight.

What is significant is that the premonition has quietly entered the system. Super Eight groups were determined by ICC ranking rather than group stage performance. India secured their second T20 World Cup in 2024 under Rohit Sharma. (Photo: Getty)

In 2024, the results did not reveal an error. India won. The draw seemed reasonable.

The mechanism existed. The fallout hasn’t exploded yet.

FIFA World Cup T20 2026: Bug Revealed

Now they have.

All four group winners are grouped in one Super Eight group. Sophomores enjoy a comparatively softer track.

First place reward? A more difficult path.

This is not a coincidence. This is a structural design.

Tragi-comedy The rise of Zimbabwe was one of the big shows of the T20 World Cup. (Photo: AP)

For more than five decades, the ICC has oscillated between clarity and chaos.

Ironically, he has known the ideal template since 1992.

The real question has never been about what works.

It was always about whether competitive integrity would be prioritized over commercial convenience.

Fifty years of evidence suggests otherwise.

Cricket deserves better.

It always was.

He probably won’t get it.

Sandipan Sharma, our guest writer, likes to write about cricket, film, music and politics. They believe they are connected.

T20 World Cup | T20 World Cup Schedule | T20 World Cup Points Table | T20 World Cup Videos | Cricket News | Live Score

– The end

Issued by:

Debodinna Chakraborty

Published on:

February 20, 2026