Taking Athletic Performance to the Next Level with Plyometrics

You’ve mastered the basics of strength training, and now it’s time to elevate your athleticism. The question isn’t whether to incorporate plyometric exercises into your routine—they’re essential for maximizing explosive power. While box jumps and depth jumps may appear similar, they engage your body in fundamentally different ways.

In this comprehensive comparison, we’ll explore the biomechanics, benefits, and best applications of both exercises. You’ll discover which movement aligns with your athletic goals, how to perform each exercise safely and effectively, and how to integrate them into a power development program that delivers results.

What Are Box Jumps?

Box jumps are a foundational plyometric exercise where the athlete starts in a standing position and explosively jumps onto an elevated platform (the box), landing softly with hips and knees bent. The height of the box can vary based on the athlete’s goals, training phase, and individual capabilities.

Key Features

- Focuses on concentric power (force production during the push-off phase).

- Reduces landing impact due to the elevated surface.

- Improves vertical jump, coordination, and confidence in takeoff.

- Commonly used in athletic preparation, warm-ups, or contrast training.

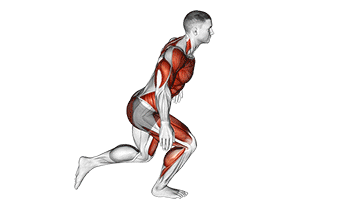

Primary Muscles Involved

- Gluteus Maximus

- Quadriceps

- Hamstrings

- Calves (Gastrocnemius & Soleus)

- Core Musculature (for stabilization during takeoff and landing)

What Are Depth Jumps?

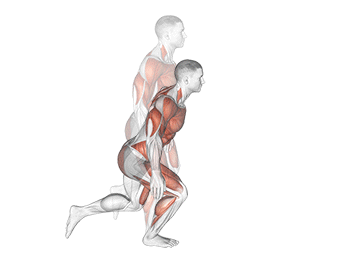

Depth jumps are an advanced plyometric drill designed to maximize the stretch-shortening cycle (SSC). The athlete steps off a platform (typically 12–30 inches), lands, and immediately rebounds upward or forward, minimizing ground contact time and maximizing reactive force.

Key Features

- Emphasizes reactive power—the ability to quickly absorb force and convert it into explosive movement.

- Targets neuromuscular efficiency by training fast-twitch motor units.

- Relies heavily on eccentric loading followed by rapid concentric action.

- Considered a high-intensity, high-skill drill, best suited for trained athletes.

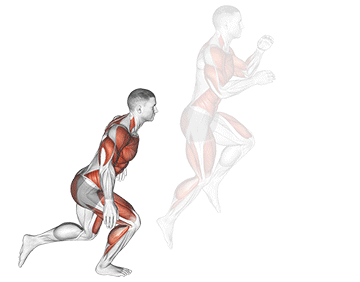

Primary Muscles Involved

Similar to box jumps, but with greater eccentric demand on the hamstrings, glutes, and calves, as well as increased neural recruitment due to fast-twitch reflexes.

The Stretch-Shortening Cycle: The Science Behind Plyometrics

The effectiveness of both exercises can be better understood through the stretch-shortening cycle (SSC), a neuromuscular mechanism that enhances force production during explosive movements:

- Eccentric Phase: The muscle is stretched under tension (e.g., landing from a drop).

- Amortization Phase: The transition between eccentric and concentric phases. This should be as brief as possible.

- Concentric Phase: The muscle shortens to generate movement (e.g., jumping upward).

- Box jumps focus less on the eccentric phase and more on controlled concentric power.

- Depth jumps are specifically designed to utilize the SSC, maximizing the efficiency and speed of the transition from eccentric to concentric contraction, making them superior for reactive power development and elastic energy utilization.

Which Builds More Explosive Power?

Depth Jumps: Pros and Scientific Support

Depth jumps generate significantly higher ground reaction forces (GRFs) and stimulate greater adaptations in muscle-tendon complex utilization, with ground contact times of less than 0.25 seconds. These qualities are essential for high-speed athletic tasks like sprinting, cutting, and rapid changes in direction.

Research shows that depth jumps can produce GRFs of up to 5 times body weight, while simpler plyometrics like box jumps typically evoke around 3.5 times body weight.

Studies by Komi and Bosco, among others, demonstrate that depth jumps more effectively improve vertical jump height, sprint speed, and rate of force development (RFD) compared to traditional jump training. Athletes with a strong foundation in maximal strength benefit most from depth jumps, as they’re better equipped to absorb and utilize high eccentric forces.

Box Jumps: Pros and Limitations

While less mechanically and neurologically demanding, box jumps are highly effective for:

- Developing power output.

- Improving coordination.

- Providing a lower-impact option for explosive hip and knee extension training.

Box jumps are particularly useful during the early stages of power development programs, for beginners, or during deload and recovery weeks. The reduced landing forces make them a safer option for athletes returning from injury.

Which Is Better for Explosive Power?

Explosive power is defined as force production over time (Power = Force × Distance / Time). Depth jumps involve a rapid transition from high-intensity eccentric landing to explosive concentric takeoff, stimulating the stretch-shortening cycle (SSC) more aggressively than box jumps.

The higher GRFs observed in depth jumps reflect a greater amount of force absorbed and produced in a short timeframe, directly translating to improved explosive power and reactive capacity. This makes depth jumps the superior choice for maximizing explosive power, provided the athlete has sufficient strength and technique to perform them safely.

Programming Considerations: When and How to Use Each

| Variable | Box Jumps | Depth Jumps |

|---|---|---|

| Intensity | Moderate | High |

| Impact Force | Lower (elevated landing) | Higher (eccentric loading) |

| Skill Level Required | Beginner | Advanced |

| Primary Focus | Concentric Power | Reactive Power, SSC Utilization |

| Best For | Teaching mechanics, low-impact power | Maximizing elastic energy |

| Program Phase | General Prep, Early Season | Peak Power Phase |

Sample Progression Model

To systematically build explosive power, consider this progression:

- Phase 1: Jump Mechanics and Concentric Power

- Box jumps (low to medium height)

- Squat jumps

- Phase 2: Load Tolerance and Reactive Preparation

- Hurdle hops

- Bounding

- Phase 3: Maximizing SSC and Explosive Output

- Depth jumps

- Drop jumps from increasing heights

This approach ensures athletes develop not only power but also control, timing, and force absorption, reducing injury risk.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

Box Jumps

- Jumping as high as possible and landing in a deep squat—this defeats the purpose by exaggerating landing rather than takeoff.

- Letting knees cave inward during takeoff or landing.

- Over-relying on momentum (arm swing) instead of leg drive.

Depth Jumps

- Spending too much time on the ground between landing and jumping—this negates the benefits of the SSC.

- Dropping from a box that’s too high, leading to poor technique or injury.

- Landing with a stiff ankle-hip-knee complex, leading to energy leakage.

Conclusion: Choose the Right Tool for the Right Goal

In summary, both box jumps and depth jumps are valuable tools for developing lower-body explosiveness, but they target different ends of the power development spectrum:

- Box jumps are better for teaching explosive movement patterns with reduced joint stress, making them ideal for beginners, rehabilitation phases, and general preparation.

- Depth jumps are better for trained athletes aiming to maximize reactive power and neural adaptations, but they require precise programming and strength readiness to avoid injury.

Rather than choosing one over the other, advanced performance programs should strategically incorporate both across different training cycles to develop holistic athletic performance—from raw power production to elite-level reactivity.

References

- Henryk Kole, Władysław Mynarski. Comparison of mechanical parameters between countermovement jump and depth jump in biathletes. PMC3590830

- Lakesha McConico. Effect of short-term training with VertiMax vs. depth jump on vertical jump performance. PMID: 18550943

- Shuzhen Ma, Yanqi Xu, Simao Xu. Effects of physical education programs on vertical jump height in healthy athletes: a systematic review with meta-analysis.

- Komi, P.V., & Bosco, C. (1978). Utilization of stored elastic energy in leg extensor muscles by men and women. Medicine and Science in Sports, 10(4), 261–265.

- Bobbert, M.F., & Van Soest, A.J. (2001). Why do people jump the way they do? Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews, 29(3), 95–102.

- Markovic, G. (2007). Does plyometric training improve vertical jump height? A meta-analytical review. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 41(6), 349–355.

- Ramirez-Campillo, R., et al. (2015). Effects of plyometric jump training on physical fitness in youth basketball players. Journal of Sports Sciences, 33(14), 1495–1503.

- McBride, J.M., Triplett-McBride, T., Davie, A., & Newton, R.U. (2002). Comparison of strength and power characteristics between power lifters, Olympic lifters, and sprinters. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 13(1), 58–66.