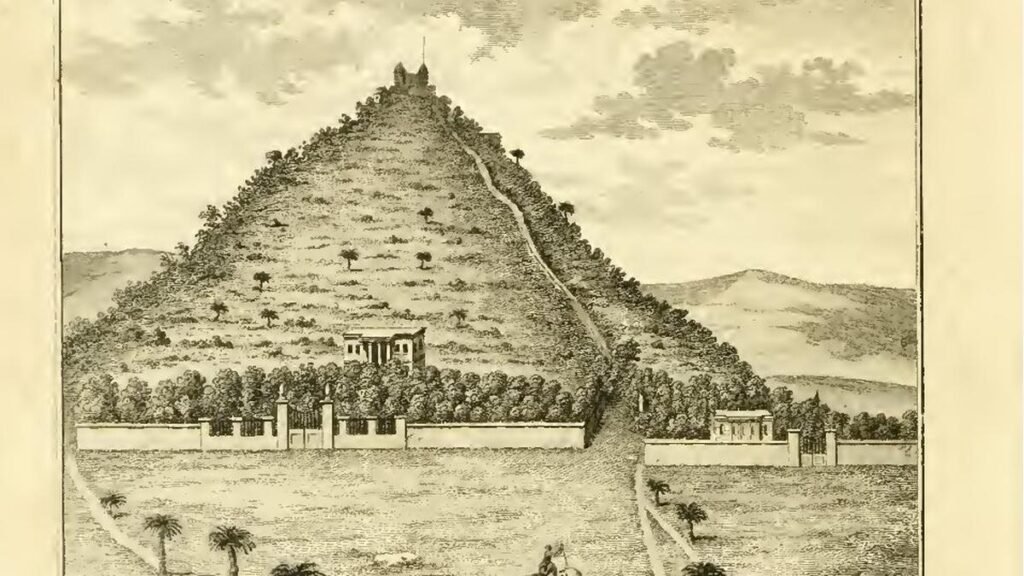

The frontispiece of the poem is an interesting depiction of the mountain | Photo credit: Special arrangement

This is my third consecutive article for this column that features a book, and I apologize for the monotony. However, it was too hard to resist writing about this poem. HD Love’s Vestiges of Old Madras never ceases to amaze and educate. Every reading brings out some kind of kick, as it did last week. This was a poem called Mount St. Thomas. It was written around 1769 or thereabouts, as it mentions the attacks on the place by Hyder Ali in 1767 and the cyclone in 1768. The poem was published anonymously in 1774 in England and is attributed to a “Gentleman from India”. The preface, anonymous, is dated January 1, 1773, and is written at Fort St. George. It is said that the author was not yet 20 years old when he wrote this poem.

Love discovers that he was Eyles Irwin, born in 1750 and arrived in Madras in 1768. “Fascinated by the natural beauty and historical associations of the mountain, he wrote (this) pastoral poem,” says Love. In Madras, Irwin, who had been in the service of the East India Company, was appointed surveyor in 1771. Five years later he was found to have done nothing and the post was abolished. He appears to have done quite well personally, having applied for and obtained from the Society eleven acres of land in the village of “Erembore” for his headquarters. Irwin was evidently a man of letters, for in 1777 he printed in England his Series of Adventures on a Red Sea Voyage. He has other poetry and prose to his credit. His death, according to love, was in England, in 1817.

The poem is available for free download at archive.org. The frontispiece is an interesting representation of a mountain, which Love says is by J. Collyer. He was very probably Joseph Collyer the younger, engraver to Queen Charlotte. He never came to India, so he had to base his engraving on sketches made by someone in Madras. If so, it depicts the hill, the steps that Petrus Uscan sponsored to the top, and the shrine at the top. On the base, beyond the compound, there are bungalows set among the trees – they may be cantonment houses for officers.

Outside the site is barren land with a few palm trees. It reminded me of Jayshree Vencatesan, India’s first Ramsar Award winner. She always maintained that the lush and dense greenery was a colonial creation in Madras, the original vegetation being palms and scrub. A camel and an elephant with attendants roam around. A tame cheetah with its trainer hunts what looks like an antelope on the other side.

On the seasons of Madras

Now for the poem: it is in three cantos, the first having 220 lines, the second 175, and the third 170. Irwin seems to be one of those who rejoices in the warm weather. “The eternal season of our eastern years,” he says, is spring, and he wonders if his countrymen at home in England, beset by winter storms and gloom, envy his good fortune. Reading after 250+ years makes us wonder because Meenambakkam, if anything, is always a degree or two warmer than the Nungambakkam weather office temperature reading. But it also supports the theory that during colonial times the mountain was considered an ideal escape from the city.

The area evidently had several mango groves, the poem paying tribute to the “blessed shade” of the trees and the abundance of “ambrosia fruit”. The poem then continues with a song in praise of the elephant and the camel. Then Irwin describes a cheetah trained to hunt being encouraged by its keeper to go after antelopes. In his notes, Love assumed that Collyer’s engraving predates the poem, but it is clear that it is a faithful representation of the poem itself. Or was Irwin inspired by the engraving and modeled his opening chant after it?

The second canto describes the legend of St. Thomas up to his martyrdom, noting how all three religions coexist here after his death—Gentoo, Mussulman, and Christian—”When men join in a friendly band, And truth rules the guileless land.” The third canto is somewhat difficult to grasp, as it is about various women of the poet’s acquaintance, then in Madras. All are addressed by their surnames – “fair Lesley, sweet Powney”, melodious Brooke and singer Taswell. Men with these surnames were certainly well known in the history of Madras. The poem itself is addressed to an anonymous lady leaving India.

All in all, it is not a great work of poetry, but it adds to the collection about the city, or at least the regions it encompasses today.

(Sriram V. is a writer and historian.)

Published – 11 Feb 2026 06:30 IST