Since the first online food order in China in 2008, delivery riders have become indispensable to urban life over the past 17 years. This workforce, often referred to as “new blue-collar workers” and driven by algorithms, has expanded to over 10 million by January 2025—equivalent to the population of Switzerland. Despite many veteran riders settling in the cities they serve, their social security status remains uncertain.

A breakthrough came in February when JD.com became the first major platform to offer “five social insurance and one housing fund” (五险一金), a comprehensive social security program covering pensions, medical care, unemployment, work injuries, maternity insurance, and housing funds. Competitors quickly followed suit: Meituan promised full benefits for stable riders by the fourth quarter of 2025, while Ele.me expanded its pilot programs.

For riders like 36-year-old Peng Ding (a pseudonym), the importance of insurance is undeniable. “A colleague of mine was in a traffic accident last summer and broke his leg. He’s been resting ever since,” Peng said. However, younger riders have reservations. At a Shanghai legislative forum on March 25, 2024, a 20-year-old delivery worker expressed his reluctance to contribute to social security. “Paying 700 yuan ($96) a month for insurance means delivering 100 extra orders. I’d rather send that money home for my daughter’s toys,” he explained, adding that he relies on the rural cooperative medical system (新农合) in his hometown.

Long Wait for Protection

At 3 p.m., after lunch, a group of Meituan riders from Anhui province gathered in front of Heyte’s shop in Shanghai’s Kaohsiung District. Many of them, some with over a decade of experience, unanimously support social insurance. “A colleague who broke his leg is still at home without any help from Meituan,” said Peng. Currently, platforms rely heavily on commercial accident insurance—Meituan deducts 180 yuan monthly, while Ele.me deducts 40 yuan for coverage. However, the risks of the job are well-documented. A 2020 report titled “Delivery Riders, Trapped in the System” by Renwu (The People) highlighted that Guangzhou traffic police penalized nearly 2,000 delivery-related violations. The hashtag #deliveryriders, one of the most dangerous jobs, frequently trends on Weibo, underscoring the profession’s challenges. For riders like Jia Hui, the compensation from platforms is minimal. “Even if you file a claim, the most you’ll get is 200 yuan ($28) a day for five days off work,” Jia said. “But what if you’re bedridden for months? No compensation, no income. We’ve seen it happen.”

Statistics show that 77% of Meituan and 75% of Ele.me riders are from rural areas. For migrant families, social insurance is a lifeline for urban integration. “Without a social security record in Shanghai, your child can’t enroll in local schools,” Jia explained, noting that many leave their children with grandparents at home. Access to healthcare is equally challenging: rural insurance offers limited coverage in cities, forcing riders to either use medical accounts in their hometowns or avoid hospitals altogether. “A simple blood test costs 500 yuan. We can’t afford to get sick,” Jia said.

When Gig Work Becomes a Lifeline

For many, food delivery started as temporary work. Yet for millions of riders across China, platforms have become an unavoidable anchor—whether by choice or necessity. The burden of caring for children, elderly parents, and other family responsibilities falls on their shoulders. “Individual riders might afford a day off, but breadwinners can’t risk skipping work,” Jia said. “Unlike salaried jobs where you still get a base pay, if we rest, there’s less money for rent or food next month. That’s why most of us never stop.”

Recent years have deepened this dependency. Before COVID-19, riders could earn 300 yuan ($41) daily—10,000 yuan ($1,380) monthly—with relative ease. Now, hitting that same target requires 12-hour shifts. Falling wages have intensified the pressure: taking time off is financially unfeasible, while switching careers seems prohibitively expensive.

Riders often come from rural counties and small towns, typically entering the gig economy with limited formal education and technical skills. While physically demanding, the job offers minimal entry requirements and quick employment. However, transitioning to other careers remains challenging, as retraining and adapting to new environments pose significant personal and financial hurdles.

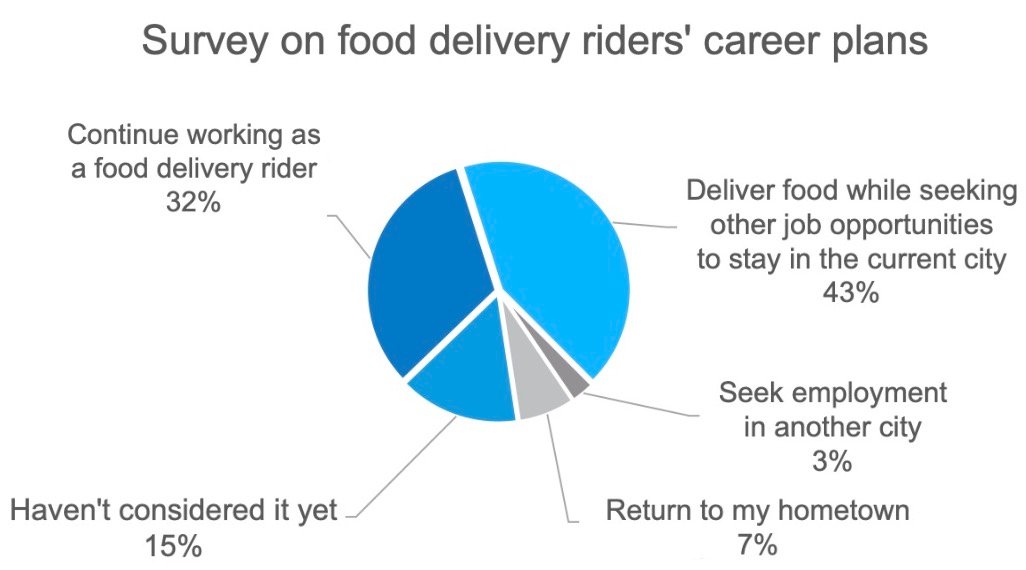

A 2022 Ele.me report revealed that 43% of delivery drivers worked in food delivery while seeking other livelihood options, while nearly a third saw no way out of the industry. As food delivery shifts from stopgap work to permanent employment for millions, the need for a comprehensive social security system is undeniable.

Hope and Skepticism

Several veteran riders I spoke with, each with years of experience across multiple platforms, reminisced about now-defunct services like Baidu Takeaway and Gearbox. While new platforms initially attract riders with subsidies, most agree that “everyone eventually prioritizes profits and becomes indistinguishable,” as Cao Lijun (a pseudonym), a Meituan rider, put it.

Cao described issues with Ele.me, such as orders being marked late and penalized despite arriving on time, and discrepancies between customer and rider apps. He also noted how subcontractors—middlemen between platforms and workers—often squeeze profits at the expense of riders.

When asked about JD.com’s recent entry into food delivery, riders viewed it as a positive step. Many praised JD’s reputation for offering local five social insurance and one housing fund, contrasting it with competitors who enroll workers in cheaper, often unusable regional plans. After concerns arose that salaries might drop due to social security costs, JD.com clarified that it would cover all contributions—including the employee’s share—for new workers.

“Many have already switched from Meituan to JD,” Cao said, though he expressed concern about the sustainability of JD’s current offer. “What if they cover all social insurance costs now but make us pay more later?”

Progress in riders’ social security could trigger broader societal changes. As the first wave of insured riders begins to retire in the coming decades, the real-world impact of these policies will become evident. Meanwhile, platforms’ evolving approach—from viewing workers as operational costs to valuing them as human capital—could reshape the priorities of the gig economy.